Morris A. Pierce

University of Rochester

Although electricity and electrification has been a subject of broad inquiry, it is important to remember than electricity provides only a fraction of the energy used in the United States. In 1990, for instance, total American energy consumption amounted to 81.2 quadrillion British thermal units, or "quads" (1015 BTUs), of which utility electric companies provided only 29.6 quads, or 36.6% of total energy consumption. Furthermore, electricity utilities are not particularly efficient, for of the 29.6 quads of energy consumed in generating electricity, nearly 70% (20.3 quads) was considered "lost during generation, transmission, and distribution." Americans use twice as much energy as residents of Germany, Switzerland, Great Britain, France, and Japan, largely a result of our insatiable appetite for electricity. Providing some slight corrective to the large number of histories of electricity, my dissertation explores the origins of district heating in America, a public utility that not only preceded Thomas Edison's electric system, but I believe had a significant influence on it. This paper is an expansion of that thesis and deals with the introduction of district steam heat and power systems in Philadelphia.

| Table 1 - Degree Days | |

|---|---|

| Minneapolis | 8007 |

| Portland, ME | 7501 |

| Milwaukee | 7326 |

| Albany | 6927 |

| Rochester | 6713 |

| Detroit | 6563 |

| Chicago | 6455 |

| Scranton | 6330 |

| Cleveland | 6178 |

| Hartford | 6174 |

| Denver | 6014 |

| Pittsburg | 5950 |

| Boston | 5593 |

| Cincinnati | 5247 |

| Harrisburg | 5335 |

| Philadelphia | 4947 |

| New York | 4868 |

| Baltimore | 4706 |

| Washington | 4122 |

| San Francisco | 2750 |

| Charleston | 2147 |

On March 5, 1889, the

Edison Electric Light Company of Philadelphia began to generate and sell

electricity from its new central station at 908 Sansom Street. Later that

same year, exhaust steam from the plant's engines was used to warm the

nearby Irving House at 917 Walnut Street, creating an additional source of

revenue that required very little cost. This was the start of what is now

the third largest district heating system in the United States (New York

and Indianapolis are 1 and 2, respectively). Edison companies in Kansas

City, Boston, and Indianapolis also began steam service in 1889 and each,

like Philadelphia's, continue to supply steam through underground pipes to

their respective downtown areas although none are still owned by an

electric utility. This practice became widespread, so that by World War I

more than 350 commercial district heating systems were operating in the

United States, all but a handful operated in combination with electric

generating stations. While about thirty of these early commercial systems

still operate, another forty have since been placed into operation.

Another 6,000 systems serve college campuses, government and military

installations, and other institutions. Commercial district heating is even

more widely used in Europe, with more than half of the buildings in

Denmark connected to central heating plants, and more than 800 Russian

cities are heated in this manner.

These facts are more or less well known, but do not provide much insight

as to why these systems developed when and where they did. The basic facts

of district heating in Philadelphia since 1889 will be summarized later in

this paper, but the primary concentration will be on the role of

Philadelphia in the history of heat and power, and in particular the

events leading up to the start of steam service in 1889. As will be seen,

that city played a large role in heat and power history.

Until the middle of the eighteenth century, colonists in America used

heating technologies they had brought with them from Europe. English

colonists built large fireplaces, filled them with huge fires, and wrote

home that "all Europe is not able to afford to make so great fires as

New-England." German immigrants, on the other hand, used closed stoves

fueled from the outside. European stove and fireplace technology had

benefited greatly from the renaissance of Roman works on the subject, and

after a thorough study of these recent improvements the first American

heating engineer introduced them to America. Benjamin Franklin's 1744

Pennsylvania Fireplace was a solid synthesis of European precedents

adapted to the American marketplace. Franklin eschewed a patent for his

invention, preferring that all be able to take advantage of it. Perhaps

more important than the invention itself, Franklin's writings on the

theory of efficient and healthful heating practices reached an audience

throughout the Western world. Although a great improvement, Franklin's

apparatus still required that each household or shop maintain one or more

fires, with the accompanying nuisance and danger. In 1749, Franklin may

have proposed heating a row of ten townhouses in Philadelphia from a

single apparatus, replacing ten fires with one.

Philadelphia also witnessed the rise of power technology in early America.

John Harding, a miller, built a windmill on Windmill Island in the

Delaware River in 1746-7 at a cost of £600. He soon died from fever, but

his son used windpower to grind grain for Philadelphians for a few years

until "it had the misfortune to have the top and sails blown off in a

violent gust, and was born in the air to Joshua Cooper's orchard on the

Jersey shore," where it became a plaything for boys. The first steam

engine built in American pumped water for a Philadelphia distillery in

1773 and despite the fact that the engine of Irish immigrant Christopher

Colles' was not particularly successful, a year later he was commissioned

by the Common Council of New York to build a steam-powered water works for

that city. There he built a Newcomen-type atmospheric engine that was

operating by April, 1776, but the whole project was interrupted by the

British difficulties of that year and was never completed. A decade later

John Fitch built a working steam engine in Philadelphia and demonstrated a

working steam boat on the Delaware, but only "reaped a reward of poverty."

Philadelphia's pressing need for water led to the construction of

steam-driven water works in 1799 under the direction of Benjamin Henry

Latrobe (1764-1820). The Philadelphia system consisted of two pumping

engines in series, with the lower pumping Schuylkill water 3,144 feet up

Chestnut street to the upper engine in Centre Square, which pumped the

water into two wooden reservoirs that held about 22,500 gallons. The two

Boulton & Watt style engines were built by Nicholas James Roosevelt

(1767-1854), who later married Latrobe's daughter. Roosevelt and Latrobe

retained rights to use the power of the engines for their own use when not

needed for pumping water. Although a significant historical milestone, the

system performed poorly, having among other faults the necessity that both

pumps be operational for water to be available. A serious fire in

September 1805 quickly depleted the small reservoir and messengers "were

at once dispatched to the Lower Engine House with pleas to start the

pumps, but the workmen were so little prepared to do so that they even had

to send a wagon out for fuel." Latrobe was appointed Surveyor of Public

Buildings in 1803 by Thomas Jefferson, but both he and Roosevelt suffered

great financial loss, and the city suffered for many years with a system

of marginal utility.

Relief came from a new water works constructed in 1815 at Fairmount that had two engines, a low pressure engine and a high pressure engine built by Oliver Evans at his Philadelphia Mars Works. The high pressure engine demonstrated the superior fuel economy that Evans had promised and in 1816 another of his engines replaced the low pressure engines in the original waterworks. Watt's warnings about the dangers of high pressure steam, however, were made all too manifest as Evans' boiler exploded twice, once killing three men. Preventing such explosions became a major public issue, but the wide use of high pressure steam engines and boilers on a large scale meant that newspapers and engineering journals would be filled with accounts of explosions for many decades. The advantages of the high pressure engine were not limited to efficiency, for Evans noted that the significant heat remaining in the exhaust steam could then be used for process and space heating. Evans' included this feature in his licenses and it was commonly incorporated. This ability to efficiency combine heat and power generation in a single process was to be of inestimable advantage to the future of steam power.

Philadelphia inventors

were also improving the efficacy of heating apparatus while others such as

Marcus Bull were examining the heating contents of fuels. Although the

potential advantages of steam heating had been advertised by men such as

Matthew Boulton and Benjamin Thompson, Count of Rumford, in the early

1800s, it was rarely employed unless a boiler was required for power

generation. Stoves and fireplaces remained the only alternative until the

introduction of hot air furnaces by inventors such as Daniel Pettibone, a

Massachusetts mechanic who moved to Philadelphia around 1809 and is listed

in city directories as an artist and edge tool maker. He patented a

"rarifying air stove" in 1808, which is promoted for use in "warming and

ventilating hospitals, churches, colleges, courts of justice, dwelling

houses ... gun-powder and other manufactories, banking houses &c. with

or without the application of steam." Pettibone petitioned Congress asking

"the adoption of its use in the capitol and other public buildings of the

government in Washington." The matter was referred to Latrobe, who

reported "that a room of the size of the hall of Representatives cannot be

warmed in any manner less expensive, and that the plan proposed by the

petitioner is ingenious and practicable, and meriting the attention of

Congress." Representatives found the atmosphere of the hall so injurious

to health that it was "impossible for them to keep their seats long at a

time." A bill was reported to provide appropriations to install

Pettibone's apparatus, but like Colles' waterworks was interrupted by

unwelcome British visitors. The matter was addressed again in 1817 and

installed the following year. Pettibone died shortly thereafter without

being paid and his son petitioned Congress on the matter in 1848, at which

time the House noted that because the apparatus had "great advantages,

both as regards it producing a uniform and healthy atmosphere throughout

the hall, and its manifest economy, it has continued in use ever since."

Latrobe also had a Pettibone furnace installed in the White House in 1813.

Pettibone's hot air apparatus in the Capitol remained in use until the

late 1850s, when two new wings were added. Each had steam heating

apparatus designed by Joseph Nason (1815-1872) of New York, including

separate basement boiler plants. Nason, originally from Boston, had gone

to England in the 1830s seeking backing for an improved gas lighting

burner, but finding no interest instead ended up installing heating

systems for fellow American Angier March Perkins (1799-1881), son of Jacob

Perkins (1766-1849). Angier, born in Newburyport in 1799, joined his

father in Philadelphia in November 1817 and stayed there about four years

before following his father to greener pastures in England. Jacob, who had

installed a hot air furnace of his own design in the Massachusetts Medical

College around 1817, prospered in England and among other interests

experimented with compressed water, which Angier adapted for use in his

1832 heating apparatus that distributed 400°F water through pipes of very

small diameter, made initially from surplus rifle barrels manufactured by

Thomas Russell's pipe manufactory. Angier's apparatus was widely used in

public buildings and quality residences through England and France, and

although generally ignored in America a few were installed, including one

by 1840 at the Philadelphia Penitentiary (probably the Eastern

Penitentiary). Angier's son Loftus (1834-1891) also has a Philadelphia

connection, marrying the daughter of Reverend William Patton of

Philadelphia in 1866.

Nason wrote about

Perkins' apparatus to his brother-in-law in Boston, James Walworth

(1808-1896), that "a success might be made of this in our cold climate,"

and the pair in 1841 bought the New York City branch office of the Russell

pipe company. The exact nature of this business is not clear, as it

account suggests it was limited to selling pipe and fittings, but they did

install a Perkins apparatus in the New York estate of Ebenezer Melleken,

which was reported to be "doing good work" forty-seven years later. In any

event, Walworth & Nason moved to Boston the following year to take

advantage of the colder New England climate. but Philadelphia, even with a

warmer climate than its early manufacturing rivals (Table 1), had

nevertheless remained the center of American heating technology through

the 1830s, evidenced by the many calorific patents granted to residents of

that city (Table 2).

After that, patents in this category, which included illumination as well

as heating and cooking, were mostly claimed by residents of New York.

Where Pettibone had moved to Philadelphia to establish his business in the

first decade of the nineteenth century, Walworth & Nason chose New

York and then Boston for their new heating business in the 1840s, probably

sealing Philadelphia's decline as a center of heating technology.

Walworth & Nason were very successful in New England, adapting their system to use exhaust steam from engines rather than hot water. Initially they used pipes imported from Russell in England, but Philadelphia's Tasker & Morris began manufacturing pipe in the late 1840s. Among the buildings heated by their system was the Eastern Exchange Hotel in Boston and several textile mills where exhaust steam was available. In 1852 the partnership dissolved and Nason moved back to New York, where he installed apparatus in several residences, including a Perkins-type hot water system in the White House in 1853. While successful, the combination of high pressures (requiring constant attention of a skilled operator) and high installation cost limited the marketplace of these apparatus to larger buildings.

| Table 2 - Calorific patents granted to Philadelphians. | |

|---|---|

| 1797 | Charles W. Peale Fireplace Thomas Hurst Wood stove |

| 1799 | Henry W. Abbett Coal stove |

| 1800 | Oliver Evans Coal stove |

| 1802 | Henry W. Abbett Wood stove |

| 1809 | Samuel Bolton Heater |

| 1811 | James Truman Cooking stove |

| 1812 | Nicholas Lloyd Wood stove |

| 1813 | Henry W. Abbett Cooking stove David Launey Fireplace Samuel Morey Fireplace George Worrell Wood stove |

| 1814 | Robert Annesley Warming houses |

| 1818 | Burgess Allison Wood stove |

| 1820 | Elijah Griffith Fireplace |

| 1822 | Robert McMinn Anthracite coal stove Philip B. Mingle Anthracite coal stove George J. Fourgeray Anthracite coal stove Julia Plantou Cook-stove |

| 1823 | John Tasker Wood stove |

| 1825 | David Asher Cooking-machine John Louvatt Anthracite coal stove Charles Weaver Coal cooking stove |

| 1828 | William & Paynter Anthracite coal stove |

Heating technology for smaller buildings underwent a significant advance with Stephen J. Gold's 1854 invention of a small automatic steam boiler. Although more expensive than the hot air furnaces they replaced, they were as easy to operate, more economical, and safer. Gold licensed several companies to manufacture this boiler, including the New York Steam Heating Company and the New Haven Steam Heating Company. Gold's boiler became a standard and was widely adopted for heating. Firms such as the H. B. Smith Company manufactured large numbers of these boilers, along with associated equipment such as radiators and valves. Agents in various cities sold and installed Gold's heating apparatus, including James P. Wood in Philadelphia. The boilers installed in the 1857 Capitol extension were higher pressure power boilers rather than heating, as they also powered the various engines in the Capitol, but the two types were becoming more similar by this time. The Capitol heating apparatus, by the way, was installed under the oversight of Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, who had grown up in Philadelphia and attended the Franklin Institute and University of Pennsylvania before attending West Point.

Among the purchasers of Gold boilers were large institutions, including the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Yale University, and numerous state asylums, hospitals, and prisons. Buildings were connected together with buried piping to expand steam service to other buildings, as in Washington when shortly after the new Capitol wings were completed, the new type of steam heating apparatus was installed in the older portion of the building. At some moment in time around 1870, unfortunately unrecorded or at least undiscovered, the merits of combining these individual building boilers together in a central boiler house were discovered. West Point in 1871 and the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Dayton in 1874, for example, did exactly this, transforming mere apparatus into a system.

Other systems were entering the urban and institutional marketplace at this time. The oldest of these was water supply, which had been used in Roman cities and little modified since then. Water was universally distributed by gravity from either a natural reservoir or an artifical one called a standpipe. Cities with fortunate geography, such as New York, were able to use gravity for the entire process, but most cities had to pump water into their reservoirs with an engine powered by either water or steam. Water pressure in distribution pipes was quite low and where higher pressures were required a pump had to be used, as was the case with fire engines. Powered by hand and later steam, fire engines were more colorful than effective, being generally of little value in fighting large fires. In the typical manner of inventions, an individual of inventive bent recognized the problem and proposed a solution.

The inventor in this case was Birdsill Holly of Lockport, New York, who had invented in the 1850s a rotary pump and steam engine that was used in the Silsby fire engine. Holly had moved to Lockport in 1859, where he formed the Holly Manufacturing Company to make a variety of machines. In the winter of 1862 several fires ravaged Lockport, which the local fire department was completely unable to check. Lockport was generously endowed with water power from the five locks of the Erie Canal and Holly connected one of his water turbines to a rotary pump, installed a network of underground pipes feeding fire hydrants, and built a pressure regulator to maintain a constant water pressure in the pipes by controlling water flow into the turbine. When a fire broke out, firemen simply connected their hose to the hydrant, opened the valve, and fought the fire. The pressure regulator responded to the pressure drop by letting more water through the turbine and instantly raising the pressure. When the firemen were finished, they would simply close the valve and the turbine would slow down.

At first, Holly made no efforts to market his invention, but soon installed another in his hometown of Auburn, New York, which also used the water for domestic purposes, and soon was beseiged by cities interested in his system, which could be powered by either water or steam engines. He obtained a patent in 1869 and the Holly Manufacturing Company was soon devoted to bulding and installing Holly' Direct Pressure Water Supply System through the country. Sales were greatly assisted by the great Chicago fire of 1871 and a large fire in Boston the following year. Holly's patent claim was of absolute simplicity and invited competition, but Holly prevailed in several patent suits. The Holly waterworks were quite famous in its day and was installed in over 2000 cities and towns in the United States and Canada. In addition to keeping urban areas from burning down, the reduction in insurance premiums was generally sufficient to return the system's cost quickly, sometimes within three years. Francis R. Upton's account of Edison's electric light in early 1880 notes that "the inventor conceived of a system which should resemble the Holly water works. As the water is pumped directly into pipes which convey it under pressure to the point where itis to be used, so the electricity is to be forced into the wires and delivered under pressure at its destination."

Manufactured gas was also widely used in American cities by the 1870s, but it is difficult to think of this service as a system. Prices were kept high to keep profits high, and with rare exceptions the potential of gas for heating, cooking, and power was completely ignored for many years. Only after serious competition arrived did manufactured gas companies realize that they have to think about something besides counting profits. Telegraph networks connected major cities, but domestic district telegraph service was only found in businesses and homes of the wealthy. The telephone arrived on the scene with a great public demonstration in 1876 at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. This exposition was also a major turning point for district heating

| Table 3 - Incorporators of Steam Heating Fuel Company of Pennsylvania, 2 July 1869. |

|

|---|---|

| D. Morris J. M. Rogers R. S. League J. C. Sturdivant J. P. Rees B. W. Oliver |

|

The Centennial Exposition was a major engineering event in itself. A remarkably complex arrangement of utilities services was required to support the many facilities. The water supply apparatus was provided by Henry R. Worthington, who offered it at no charge as an exhibit. Unable to provide direct pressure service due to Holly's patents, the Exposition supply required a standpipe, which could necessarily provide very little pressure. Conspicuously absent from the displays were the wide variety of small water motors that could be directly used with the pressure available on a Holly system. Of greater interest, however, is the extensive system of steam distribution piping required to connect boilers with the large number of small steam engines on display. Although the large Corliss engine provided the bulk of power in the main Machinery Building, 6,268 feet of steam pipe was required to provide steam to the various smaller engines.

Holly did not have a display at the Exposition, and it is likely that he visited Philadelphia on one of the special Exposition trains from Lockport in that centennial summer. Several attempts had been made to install public steam systems before Holly. Proposals were made in England to use Perkins apparatus to heat large blocks of workers' housing, but none was apparently used in this manner. The Steam Heating Fuel Company of Pennsylvania was chartered by the state legislature in 1859 (Table 3) and John A. Coleman of Providence patented a district steam system in 1873, but nothing appears to have come of either. From whatever germ the idea of district heating arose, Holly that summer started digging up his back yard to test the idea of selling steam through an underground piping system. He successfully warmed a house 500 feet away and in January 1877 convinced several Lockport residents to form the Holly Steam Combination Company, which held its first meeting in the bookstore owned by its first president, Samuel Rogers. An experimental system was installed that year in Lockport and after a winter's trial was declared a success. Four more systems were installed in 1878 and ten more the year after. Holly's water works had given him a solid reputation and potential investors and customers soon filled the hotels of Lockport. Rights to New York City were obtained by Francis B. Spinola, but either his financials backers or other New York investors required an independent engineering evaluation of the Holly steam system, for which they engaged the services of Herman Haupt, a Philadelphia engineer of wide, if not always successful, experience.

| Table 4 - Philadelphia Steam Supply Company incorporators, 5 April 1882. |

|

|---|---|

| Edward Hoopes Charles M. Foulke Charles O. Baird William H. Perry Winthrop Smith Henry C. Davis |

|

General Haupt arrived in Lockport at the end of January 1879 to investigate the system and prepare his report, which was published by the company as a promotional brochure which is clearly presented as the work of a disinterested professional. It neglects to mention, however, that Haupt had other business dealings with Holly, specifically the purchase of two Holly pumping engines the previous November for the Tide Water Pipeline Haupt was building in north central Pennsylvania. A Lockport newspaper also reported that Haupt was negotiating for the rights to install the Holly steam system in Philadelphia. Haupt was generally insolvent by this time, however, and district steam service in Philadelphia would have to wait for more substantial backing. Haupt had no further career in the field of steam heating, pursuing other opportunities such as building railroads and raising Angora goats.

The Holly Steam Combination Company and Holly's patents were purchased by a group of New York investors in late 1881 and more than thirty cities had Holly steam systems operating by 5 April 1882, when the Philadelphia Steam Supply Company was incorporated with a capital stock of $1 million. Cornelius H. Gold held 18,000 of the 20,000 shares with the remainder held by six Philadelphia investors (Table 4). Like other public utilities, steam companies required both a state charter and a franchise to use the streets. The Philadelphia company petitioned the Common Council for a franchise on 5 May and the matter was referred to the highway committee. Nothing happened until January, 1883, when the committee held a hearing on the matter. John C. Wilson of the firm of Wilson Brothers & Company reported that he had examined Holly systems in several cities. He thought the system "entirely feasible and safe, if good material were used and the necessary precautions taken." D. F. Bishop, a Lockport physician and president of the American District Steam Company, testified that only a single accident had ever occurred on a Holly steam system, that in Lynn, Massachusetts the prior summer. A competitive system installed in New York City had also suffered explosions, but the Holly firm in that city, the New York Steam Company, had had no incidents.

| Table 5 - Pennsylvania steam heating companies formed in the 1880s, with termination year. |

||

|---|---|---|

| 1883 | Clearfield Philipsburg Bellefonte |

1956 1957 1916 |

| 1884 | Williamsport Lock Haven |

1917 1916 |

| 1886 | Wilkes-Barre Tyrone Harrisburg |

1990 1946 * |

| 1887 | Hazelton Reading Bloomsburg |

1920 1968 1968 |

| 1888 | Attleboro Pottsville Allentown Lebanon |

1920 1972 1968 1966 |

| 1889 | Philadelphia | * |

| * = Still Operating | ||

The hearing was adjourned, but no action was forthcoming by the committee. Quite frustrated, the company filed suit against the city in June 1883 claiming that the state charter compelled the city to grant them the privilege of using the streets. The Common Council referred the matter to a joint committee on law and highways, which held hearings on the matter through the summer and finally reported the ordinance with a favorable recommendation, with the proviso that the "pipes shall be used only for the transmission of heat." Many councilmen thought the privileges were still too broad, however, and attempted to limited the franchise area to the district bounded by Broad street, the Delaware river, Vine, and Spruce streets. On 16 November the ordinance was defeated by a vote of eight for and eighteen against. Outside of Philadelphia politics, the critical issue was the explosions suffered by the systems in Lynn and New York. The former had been installed in late 1880 and was the first of a new Holly design utilizing two distribution pipes. The first, connected to the boiler plant, carried 80 pound steam to various engines in small shops. The steam exhausted from the engines was distributed at very low pressure through a second set of pipes. Several reasons are possible for the Lynn explosions, all of which occurred on the high pressure line, but the principal fault must reside with the local management, which had clearly tried to take every shortcut possible in installing the system, which went out of business in 1883. The troublesome company in New York was the American Heat and Power Company, which survived only a few months and was in receivership on early 1883. The New York Steam Company was really not a standard Holly design but rather greatly modified by their chief engineer, Charles E. Emery. The New York Steam Company were to have their share of problems, including exploding pipes, at the end of the 1880s.

The company continued to press its suit against the city and the following May advised Mayor King of its intention to commence work in order to protect its charter rights, which required the work to be underway within two years. Pipes were to be laid in the district bounded by Fourth, Ninth, Vine, and Market streets, to be supplied by a steam plant in the rear of 625 Arch street. Mayor King replied that any attempt to open the streets without permission of the council would be checked. There the matter rested until 21 June 1884 when Common Pleas Judge Mitchell ordered the city to draft regulations permitting the company to fulfill its charter privileges. The highway department's board of supervisors drafted the regulations and approved the company's plan in late August. Two weeks later Sanitary Engineer reported that the steam plant on Arch was under construction, but nothing more is known and Philadelphia Steam Supply Company disappears.

During the time that the Philadelphia Steam Supply Company was attempting to pry a franchise from the Common Council, several other Pennsylvania cities installed Holly steam systems (Table 5). The fact that many of these systems operated for many decades is substantial evidence that the technology was fundamentally sound. Efforts to establish steam service in Philadelphia continued throughout the 1880s, including the 1886 Keystone Light and Power Company was chartered to supply "light, heat and power to the inhabitants of the city of Philadelphia and vicinity by electricity and steam" and built a power station, but it never applied for a franchise to provide steam service and apparently never did so. In August 1887 the Steam Heating Company of Philadelphia was chartered with a capital of $400,000, but for some reason did not aggressively pursue the installation of a system. The Philadelphia Heating Company, chartered in May 1888, appears to have been connected with the National Superheated Water Company, which was then operating an extensive high temperature hot water system in Boston. The company applied for a franchise in the area between Arch and Pine streets, and between Fifteenth street and the Delaware, but the Common Council refused to allow a pressure greater than thirty pounds in the piping, effectively frustrating the high pressures (more than 300 pounds per square inch) required by this system. The piping of the Boston works failed in November 1889, to the financial distress of its principal backer, telephone magnate Theodore Newton Vail.

An ordinance was obtained by the Mutual Steam Heating Company of Philadelphia on 12 February 1889 to lay pipes in the territory bounded by Thompson, Allegheny, Fifth, and Twenty-fourth streets, just north of downtown Philadelphia. Engineering News reported that the company "is said to be mainly made up of city politicians," which is certainly possible in that city, yet if true would not explain why the ordinance excludes the major business district. The company was given one year to commence work, which was later extended by six months, but again no evidence has been found to suggest that the company actually operated.

Another ordinance granted privileges to the West Philadelphia Steam Heat Company in April 1892 for the area bounded by Thirty-seventh, Fiftieth, Woodland, and Market streets west of the Schuylkill river. Again, nothing else suggests that this company actually operated. The Overbrook Steam Heat Company was granted steam privileges in the Twenty-second ward in November 1893 and installed a system that provided steam to about 300 customers in the mostly residential neighborhood developed by the Carpenter Land and Improvement Company in Germantown until 1963. Similar systems serving suburban areas were also built in Wayne (1890-1948), Overbrook (1894-1973), Norristown (1902-1920), West Chester (1902-1972), and Chester (1889-1920?).

| Growth of the Philadelphia Steam System | |

|

|

| 1921 | 1935 |

|

|

| 1950 | 1975 |

As has been mentioned, the Edison plant on Sansom began supplying steam to adjacent buildings in 1889. This practice was adopted by several hundred electric utilities over the next two decades, but its use in Pennsylvania was stifled because the state legislature outlawed it for any company incorporated after 8 May 1889. Pennsylvania's generator corporation act of 29 April 1874 permitting companies to be formed for "the manufacture and supply of gas, or the supply of light or heat to the public by any other means." For reasons not clearly understood, the Secretary of State felt that the new electric companies were taking advantage of this and somehow violating the single purpose intent of the 1874 law. This "loophole" was corrected in 1889 when the law was amended to permit "the manufacture and supply of gas, or the supply of light, heat and power by means of electricity, or the supply of light, heat or power to the public by any other means." Entrepreneurs were able to get around this provision by forming a separate companies to distribute the electricity and steam, but it clearly had the effect of stifling growth of cogeneration in Pennsylvania for many years. The Edison company had been incorporated in 1886 and was not affected by this law.

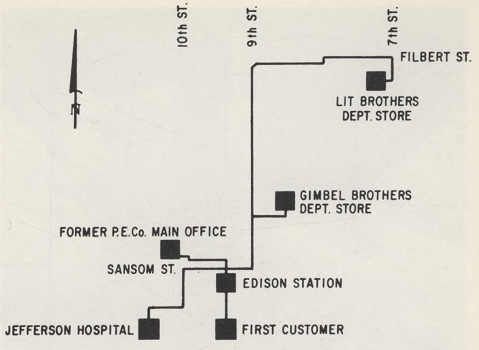

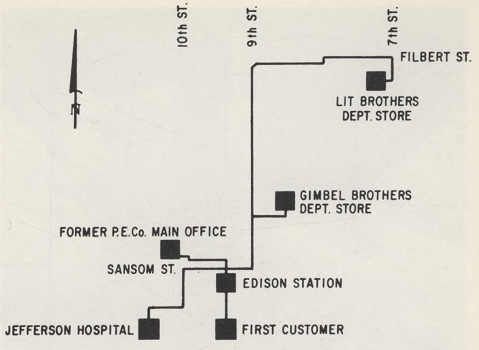

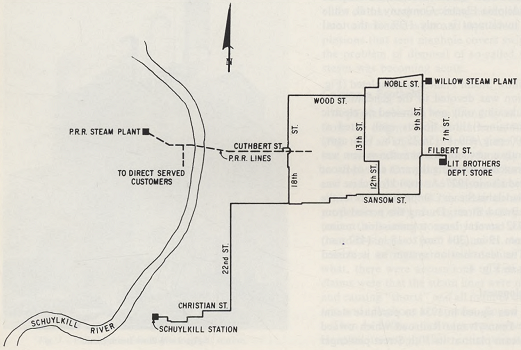

Over the next several years, additional pipes were laid to warm other nearby buildings while the Edison company became part of the Philadelphia Electric Company. In the first deacade of the new century selling electricity to large buildings was very difficult because most found it advantageous to make electricity in their steam heating plants. New buildings often had such plants built into them, making it impossible for the utility to add these large users to its system. In 1906, nearby Thomas Jefferson Hospital agreed to abandon its isolated plant and purchase power from Philadelphia Electric only if continuous steam service was also provided. Similar arrangements were made with Gimbles in 1910 and Lit Brothers in 1921, and by the mid-1920s when the Edison station was replaced a more modern plant, the company felt a "moral obligation" to continue the steam service (Figure 1).

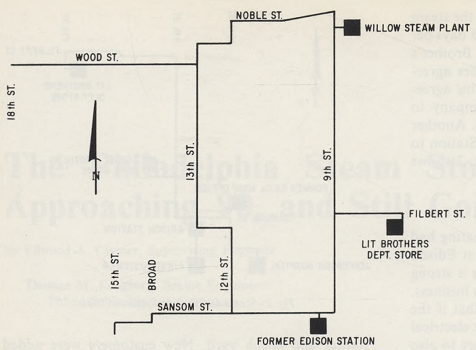

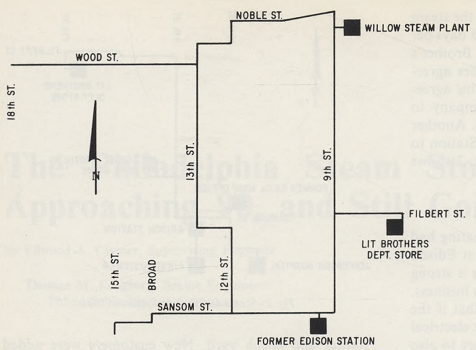

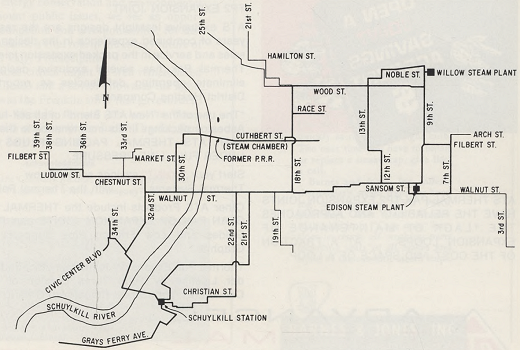

A general steam franchise was obtained in 1927 to serve the city east of Broadway street, replacing the individual street crossing permits that had been used previously. A new steam plant was built at Ninth and Willow in 1927 and major additions were made to the distribution system (Figure 2). Another firm, the Philadelphia Steam Company, obtained a franchise two years later for the area west of Broad street, but a controlling interest in this second company was purchased in 1931 by Philadelphia Electric. By 1950 the Schuylkill electric plant provided the majority of steam to the system. In 1957 the original Edison station on Sansom street was rebuilt as a steam plant, and in 1964 the University of Pennsylvania was added to the system (Figure 3). Philadelphia Electric sold its steam system in January 1987 for $30 million and it is now owned and operated by Philadelphia Thermal Energy Corporation, a subsidiary of United Thermal Corporation.

Although district heating was slow to develop in Philadelphia, it would have been impossible for the Philadelphia Electric Company to displace the many isolated electric plants and build a large electric system without it. The requirement to supply steam always provided an anchor that kept some electric generating plants in Philadelphia when the trend was to built large mine-mouth coal plants, hydro-electric facilities, or nuclear stations. The Philadelphia Thermal Energy Corporation is fundamentally an isolated plant, albeit a large one, generating electricity as a by-product of steam production and selling it to Philadelphia Electric. As large networks of power become economically and environmentally untenable, such isolated plants are again playing a major role in the power marketplace.

The system was sold to Catalyst Thermal Energy Corporation on January 30, 1896 for $30 million. It was later acquired by Trigen and is now owned by Vicinity Energy.

References

1976 "The Philadelphia Steam Story…

Approaching 90, and Still Going Strong," by Ellwood A. Clyme4 and

Thomas M. Loughery, District Heating 61(4):24-29 (April, May, June

1976)

1976 "Philadelphia

Energy Conservation Plan," by Elwood A. Clymer, Jr., Proceedings of

the International District Heating Association 67:104-111 (1976)

Overcoming Institutional Barriers to Recovery of Energy from Municipal

Solid Waste

© 1995-2023 Morris A. Pierce