|

Chronological List of District Heating

Systems in the United States |

|

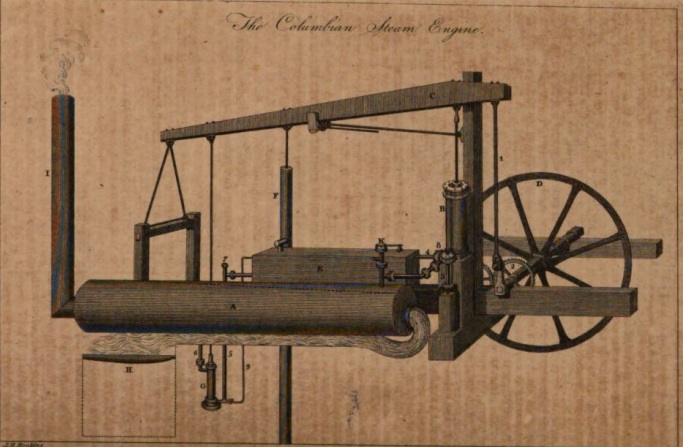

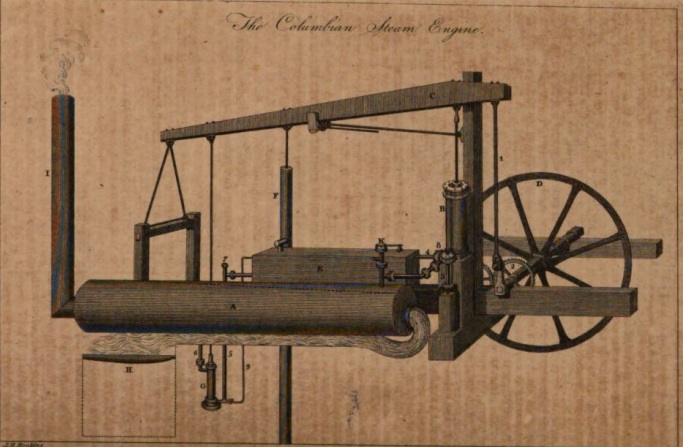

| Oliver

Evans' High Pressure Steam Engine |

The Middletown Manufacturing Company purchased a 24-horsepower high-pressure steam engine manufactured by Oliver Evans at his Mars Works in Philadelphia. The exhaust from the engine was used to heat the factory and to dress the cloth. This was the first known application of cogeneration or combined heat and power in the United States.

Several sources have repeated the false claim that Thomas Edison's 1882 Pearl Street station employed cogeneration, but the exhaust steam from its non-condensing engines was exhausted into the atmosphere after passing through feed-water heaters. Steam in that area was being provided by the New York Steam Company.

The first electric company known to sell exhaust steam for heating was the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of Lawrence (Mass.) in 1885. Many electric companies were doing so by the 1890s.

Adoption of steam in American factories came slowly due to the wide availability of water power, but became the norm later in the 19th Century due to its being more reliable, especially in cold weather.

References

1810 "An

Act Incorporating the Middletown Manufacturing Company," October

1810

1812 "Account

of the steam engines of Oliver Evans," by Oliver Evans, Archives

of Useful Knowledge 2(4):362-369 (April 1812)

Page 364: 5th. One at Middletown, Connecticut; the property of the

Middletown Woollen Manufacturing Company ; twenty-four horse power,

driving all the machinery for carding, spinning, reeling, weaving,

washing, fulling, dyeing, shearing, dressing and finishing. The steam,

after doing all this, warms the house, heats water, &c. and serves

instead of oil, in dressing the cloth. It is preferred by the artist, Mr.

J. Sandford, who directs the establishment, to all he had seen in England,

after remaining there thirteen years, and seeing all the best British

steam engines. (b)

Page 367: (b) Mr. Sandford says, in a letter to Mr. Evans, “as to

the engine we had from you, it continues to perform with increasing

credit, and thus far exceeds any thing of the kind I ever saw. It is my

opinion, that it will continue superior to all other modes of constructing

steam engines ; as to all former constructions for that purpose, they are

so far inferior, in my opinion, that I would not take them as a gift,

could I obtain yours at your price.”

1813 Letter from Oliver

Evans to his son George, May 19, 1813. Reprinted in Oliver

Evans: A Chronicle of Early American Engineering, by Greville

and Dorothy Bathe (1935) page 193.

I have conceived a great improvement in the application of my

inexhaustible principle of my Steam engine I warm a factory by Conveying

the Steam by light coper pipes through all the appartments so that the

Steam condensed to water will run back to the supply pump The air itself

will condense the steam with the aid of the pressure of the Steam as the

pipe fills and the hotter the supply water is returned to the boiler to be

raised the less by the fire say 30° only the less fuel will be required

because the difference between the elastic power of Steam in the boiler

and condenser will be greater and this difference is the neat power of the

engine. For suppose the heat in condenser of the supply will be 302

degrees we raise it 30° by the fire to 332° then the power in boiler 240

lbs in condenser 120 lbs neat power 120 lb we had only taken one step in

the true path when we resisted the atmosphere please let us try 3 or 4

more steps.

So that it appears that every time we double the resistance in the

Condenser and then raise the water 30° in boiler we double the neat power

so that there is no doubt with me but that the greater the resistance to

our piston the less the consumtion of fuel

At Patapsco near Baltimore they have a copper pipe run through all their

appartments enough to condense for 100 horse power and their boiler to

make the steam sufficient for a 20 or 30 horse engine the same fuel that

they use would drive the Engine to work their Machinery is not this

astonishing that this was not sooner seen in all the 7 years since I first

calculated the above table and explained it in a book This will secure our

Steam engine 14 years perhaps longer but Mum

1833 Documents

Relative to the Manufactures in the United States, collected

by the Secretary of the Treasury, Louis McLane;

Exec. Doc. No. 308, 22d Cong., 1st sess., 1833; Report on Steam Engines

1835 "Effectual Plan of Heating Factories, &c., by Steam," by Neil Snodgrass, May 5, 1834, Mechanics Magazine 3(5):273-274 (May 17, 1834)

1838 Report on Steam Engines, by Levi Woodbury, December 13, 1838

1884 The

History of Middlesex County, Connecticut

Page 96: In 1810, a woollen mill was established on Washington

street by the Middletown Manufacturing Company. The officers were

Alexander WOLCOTT and Arthur MAGILL. This was one of the first, if not the

first manufactory that ever used steam as a motive power, in this country.

The large brick building which stood near the foot and in the rear of

Washington street, on the present site of the "deep hollow," was built

originally for a sugar house. It was 40 by 36 feet, five stories high,

with an extension 40 by 20 feet, which was used as a dye house. The

building was fitted up with a 25-horse power engine, and wood was the only

fuel that could be obtained at this time. The company employed from 60 to

80 hands, with a capacity for 100. About 40 years per day of fine

broadcloth were produced, which yielded an income of upwards of $70,000

per year. Although the cost of fuel was a serious drawback, the company

must have made large profits at first, for the Washington Hotel, corner of

Main and Washington streets, now the Divinity School, and the large brick

hotel, subsequently used by Mr. CHASE as a school, were the outgrowth of

this enterprise. The sudden fall in goods at the close of the war of 1812,

caused a serious embarrassment, and not long after, this company ceased to

do business.

1885 Bulletin

for Agents No. 7, The Edison Company for Isolated Lighting,

August 19, 1885. Edison Mircofilm Reel 097, Archive.org

Page 14: Besides selling the current for lighting, they have

connected with their station some 20 motors; they are supplying current

for the regulation of clocks, and their exhaust steam is sold for heating

and other purposes.

1885 Steam

Using: Or, Steam Engine Practice, by Prof. Charles Augustus

Smith

Page 289: In the United States the application of steam for heating was

begun in 1842, by J. J. Walworth and Joseph Nason, and the first building

heated by steam was a cotton mill in Portsmouth, N. H. The exhaust steam

from the engine was used very successfully, and from that time to the

present there has been a steady increase in the number and magnitude of

the works constructed for this purpose. This has been owing to the

severity of the climate and the large number of new buildings erected in

the rapid growth of the country. The business of the Walworth

Manufacturing Company, of Boston, Mass., in constructing steam heating

plant is now $1,500,000 per annum, and there is in the United States a

business estimated by competent authorities at $6,000,000 per annum, which

has for the past 30 years averaged $2,000,000 per year. In other words,

there is now invested in the United States about $60,000,000 in steam

heating apparatus, so that in this subject there is no lack of precedents

for many kinds of apparatus.

1896 Transactions

of the American Society of Heating and Ventilating Engineers

2:132 (1896)

Page 132: If any one on a chilly day would look at the Edison

station in Pearl street and watch the immense clouds of steam going up

from the plant, those who have anything to do with steam would immediately

see very big piles of coal disappearing in front of them all the time.

1904 "Edisonia,"

a Brief History of the Early Edison Electric Lighting System,

by the Association of Edison Illuminating Companies.

Page 65: Pearl Street station. The engines were non-condensing

and exhausted into the atmosphere through exhaust feed-water heaters.

Page 167: The steam pipe is 5 inches inside diameter, and thoroughly

lagged; the exhaust pipe, also 5 inches in diameter, leads to the air

through a Berryman feed-water heater.

1908-1910 The Isolated Plant, Volume 1 & 2

1913 Thirty

Years of New York, 1882-1892: Being a History of Electrical

Development in Manhattan and the Bronx

Page 124: The engines were non-condensing and exhaust into the

atmosphere through exhaust feed-water heaters.

1927 "The

First Electric Station for Light and Power," by John W. Lieb, Brotherhood

of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen's Magazine 82(11):419-421

(November 1927)

The station as provided with a traveling crane and exhaust feed-water

heaters, exhausting into the atmosphere, as the plant was non-condensing.

1935 Oliver

Evans: A Chronicle of Early American Engineering, by Greville

and Dorothy Bathe.

Page 224: The largest manufacturing of fine cloths and cassimeres in

operation: in New England was that of “Middletown Woolen Manufacturing Co”

owned by Isaac Sanford and others in Connecticut. It made daily from 30 to

40 yards of broadcloth which sold at around $10 a yard. The mill employed

one of Evans’ steam engines, of twenty four horse power which drove all

the machinery for carding, spinning, reeling, weaving, washing, fulling,

dyeing and finishing, with the aid of a brush machine, as well as for

warming the building.

1940 A

Power History of the Consolidated Edison System, 1878-1900, by

Payson Jones

Page 206: The engines were non-condensing and exhausted into the

atmosphere through exhaust feed-water heaters.

1941 Menlo

Park Reminiscences Vol 3 Of 3 By Francis Jehl | also here

|

Page 1047: Cross-section of the Pearl Street station showing the

steam exhaust stack through the roof.

Page 1051: The engines were noncondensing and exhausted into the

atmosphere through exhaust feed-water heaters.

1966 "Steam and Waterpower in the Early Nineteenth Century," by Peter Temin, The Journal of Economic History 26(2):187-205 (June 1966)

1969 Early stationary steam engines in America:

a study in the migration of a technology, by Carroll W.

Pursell | also here

|

Pages 83-84: One of the first engines area was built by Oliver Evans

in 1811 for the Middletown Woollen Manufacturing Company of Connecticut.

This engine was in operation by May 1811 and drove “all the machinery for

carding, spinning, reeling, weaving, washing, fulling, dyeing, shearing,

dressing, and finishing.”4 6 After a year of operation, the English “chief

artist” of the mill wrote Evans that the engine was so far superior to

those of previous designs, that “I would not take them as a gift, could I

obtain yours at your price.” Evans considered this high praise from a man

who had “been in England 13 years, engaged in manufactories wrought by

steam engines.” Since Evans’ engine did not condense the steam it used,

the steam was available for further use after its expansion. In the

Middletown mill, it was used to heat the building during cold weather and

was also “applied in connection with the brushing machine in finishing

their cloth, without adopting the method of oiling and hot pressing as is

commonly practiced in England. In this method of finishing,” it was

explained, “the cloth does not require sponging before it is made up.

1970 "The

Infancy of Central Heating in the United States: 1803 - 1845," by

Benjamin L. Walbert, III, Bulletin of the Association for

Preservation Technology 3(4):76-88 (1971)

Page 80: Steam heating appears to have been the most popular type of

central heating used in textile mills: installations were rare, to be sure

prior to 1845. The first steam installation appears to have been made in

the Middletown Woolen Manufacturing Company in Connecticut in 1812.

Exhaust steam was passed through copper pipes. A similar system using

copper pipes was used to warm a factory in Baltimore in 1813.

1972 "Technological Innovation in the Woolen Industry: The Middletown Manufacturing Company," by Howard Dickman, Bulletin of the Connecticut Historical Society 37(2):52-58 (April 1972)

1980 Oliver

Evans: Inventive Genius of the American Industrial Revolution

by Eugene S. Ferguson.

Page 47: Evans’s ability to identify problems as well as to solve

them was demonstrated in the installation of a steam engine in the

Middletown (Connecticut) Woolen Manufacturing Company mills. In many

factories, high-pressure steam engines were exhausted into vats or other

vessels that required hot processing liquids; in Middletown, Evans used

the exhaust to heat the mill buildings, an original and immensely useful

idea. The exhaust was led through a network of small pipes that acted as

steam radiators.

1993 Networks

of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880-1930, by

Thomas Parke Hughes

Page 43: Pearl Street station. The exhaust from the steam

engines passed through feed-water heaters and then into the atmosphere.

1995 "A History of Cogeneration Before PURPA," by Morris A. Pierce, ASHRAE journal 37(5):53-60 (May 1995) | pdf |

1998 Turning

Off the Heat, by Thomas R. Casten

Page 5: The process is called "combined heat and power" (CHP), it is

not a new idea and was in fact utilized by Thomas Edison's very first

commercial electric-generating plant on Pearl Street in Manhattan in 1881.

Page 45: Edison recovered the steam left over from this early

generator and piped it to nearby buildings to sell for heat in the winter.

[Note: This book by my friend Tom Casten is the source of the bogus

claim that cogeneration was employed at the Pearl Street station, which

has unforunately gone viral.]

2001 "An

Early History Of Comfort Heating," by Bernard Nagengast, ACHR

News, November 6, 2001

There was no such resistance to steam in the U.S. due to the ready import

of ideas and equipment from England. A number of steam heating systems

were installed after 1810, one of the earliest at a factory in Middletown,

CT, in 1811. This system used exhaust steam from a high-pressure steam

engine; thus the heating was essentially free.

2008 Carrying the Mill: Steam, Waterpower and New England Textile Mills in the 19th Century, by Marti Jaye Frank, doctoral dissertation, Harvard University

.

© 2024 Morris A. Pierce

Si