|

Chronological List of District Heating

Systems in the United States |

|

|

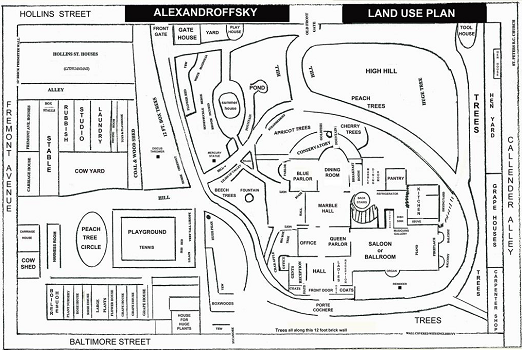

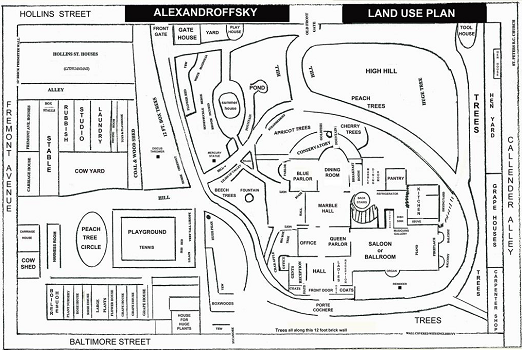

| Alexandroffsky House | Alexandroffsky Site Plan Note the boiler house close to the corner of Baltimore Street and Freemond Avenue. |

Thomas deKay Winans (1820-1878) was the son of Baltimore engineer and railroad equipment manufacturer Ross Winans. Early in his career, Thomas Winans traveled to Czarist Russia to plan and construct the Moscow-St. Petersburg railway, a venture that paid handsomely. In 1847, Thomas Winans boasted he was building 134 locomotives and 1,200 cars, and completing "a mile of cars a month!" Describing the project in 1858, travel writer Bayard Taylor claimed the route was “as straight as a sunbeam.” Returning to Baltimore in 1850, Thomas Winans acquired a block square property formerly owned by the McHenry family on Hollins Street; by 1852 and on it built a magnificent home which he called Alexandroffsky after the city in Russia where he lived during his stay there.,

Winans' estate of twenty buildings was heated by a hot water system based on systems common in Russia. Built by Hayward, Bartlett & Company, the system used natural circulation to warm some 20,000 square feet of coils in some twenty buildings with a cubic content of half a mile. The heating coils were placed beneath the floors of the rooms, and fresh air was drawn over them through holes in the floorboards. The current of air, which passed finally through ceiling ventilators, was created by a prominent tall stack, the whole arrangement constituting an exhaust draft system quite the opposite of the modern blower system. The plant operated most efficiently, with a daily consumption of some 800 pounds of coal.

He first slept in the building on February 24, 1852. The estate passed to his daughter after he died and the house was torn down in 1929.

References

1801 The

Picture of Petersburg, by Heinrich Friedrich von Storch

Page 50: The Tauridan Palace. The heat is maintained by

concealed flues practised in the walls and pillars, and even under the

earth leaden pipes are conveyed, incessantly filled with boiling water.

1823 "Chaleur,"

Dictionnaire technologique, ou Nouveau dictionnaire universel des arts

et métiers et de l'économie industrielle et commerciale 4:326-378

(1823)

Page 377: Bonnemain

1827 "Incubation Artificelle," Dictionnaire technologique, ou Nouveau dictionnaire universel des arts et métiers, et de l'économie industrielle et commerciale 11:160-169 (1827)

1828 The

Gardener's Magazine, and Register of Rural and Domestic Improvement

3:430

It is probable, also, that the circulation of hot water in the

conservatory of the Palace of Taurida, mentioned by Storch, in his

Description of St. Petersburgh, as having been in use in the time of

Prince Potemkin was effected by some French engineer who had seen the

invention of M. Bonnemain.

1835 "Observations on the comparative Advantages and Disadvantages of the various Systems of heating by Hot Water now in Use; and on the System in general," by Censor, The Architectural Magazine and Journal of Improvement in Architecture, Building, and Furnishing and in the Various Arts and Trades Connected Therewith 2(91):407-422 (September 1835)

1838 "Review

of A practical Treatise on Warming Buildings by Hot Water and an Inquiry

into the Laws of radiant and conducted Heat : to which are added,

Remarks on Ventilation, and on the various Methods of distributing

artificial Heat, and their Effects on Animal and Vegetable Physiology,

by Charles Hood," The Gardener's Magazine, and Register of Rural

& Domestic Improvement 14(94):50-54 (January 1838)

Page 50: A short sketch of the origin and history of this mode of

heating is given, in which we regret to find that the first inventor.

Bonnemain (see Gard. Mag., vol. iv., for 1828), is not once mentioned. In

Petersburg, also, during the time of the Empress Catherine, the immense

conservatory built by Prince Potemkin, as a part of the Taurida Palace,

was heated by hot water, which, Storck informs us, was circulated both

above and under ground, in leaden pipes.

1838 "Official Report Made to Charles Boyd, Esq., Collector of Her Majesty's Customs, for the Information of the Honourable Board of Commissioners, upon Bernhardt’s Stove-Furnaces," by Andrew Ure, The Architectural Magazine and Journal of Improvement in Architecture, Building, and Furnishing and in the Various Arts and Trades Connected Therewith 5(1):31-36 (January 1838)

1839 "Incubation, Artificial," A Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures, and Mines, Etc, by Andrew Ure 663-665 (1843)

1941 Iron

men and their dogs, by Ferdinand C. Latrobe

Pages 11-13: At that time Jonas Hayward was pointed out as “the principal

in introducing most successfully in many of the largest cities in this

country the system of heating public and private buildings with Hot

Water." Notable among the innumerable early installations that we have

discovered were those in the United States Treasury at Washington and the

Custom Houses at Norfolk and Alexandria, Virginia, Baltimore, Maryland,

Portland, Maine, and Buffalo, New York. Probably the firm's unique

installation was that at Alexandroffsky, the palatial residence of Thomas

Winans, who, in 1843, had been called by the Czar of Russia to build the

government's railroad, an extremely lucrative enterprise. In 1853,

Thomas Winans erected his mansion upon a part of the former McHenry

property, at Baltimore and Fremont Streets. The estate was supplied with

many conveniences of the family's invention, including the revolutionary

heating system, built by Hayward, Bartlett & Company, which connected

with some 20,000 square feet of coils in some twenty buildings with a

cubic content of half a mile. The heating coils were placed beneath

the floors of the rooms, and fresh air was drawn over them through holes

in the floorboards. The current of air, which passed finally through

ceiling ventilators, was created by a prominent tall stack, the whole

arrangement constituting an exhaust draft system quite the opposite of the

modern blower system. The plant operated most efficiently, with a daily

consumption of some 800 pounds of coal.

1998 Russia

enters the railway age, 1842-1855, by Richard Mowbray Haywood

Includes several references to Thomas Winans.

2006 "Jean Simon Bonnemain (1743-1830) and the Origins of Hot Water Central Heating," by Emmanuelle Gallo, paper presented at the Second International Congress on Construction History, Queens’ College, Cambridge, 29 March-2 April 2006, Construction History Society 1:1045-1060 (17 June 2006)

2011 "Alexandroffsky,

The Crimea and Orianda: Thomas Winans in Baltimore County," by John

McGrain, History Trails of Baltimore County 42(3):1-12 (Winter

2010-2011)

P

2011 "A

world behind a wall," Baltimore Style, April 19, 2011

Like his neighbors, Alexandroffsky’s owner, Thomas Winans, also had

railroad connections. The son of Ross Winans, an inventor responsible for

designing the B&O’s first locomotive (whose St. Paul Street home was

designed by renowned architect Stanford White), Thomas Winans made much of

his fortune in Russia, where in 1843, Czar Nicholas I gave him, his

brother and two partners (one the father of the artist James McNeill

Whistler) a $5 million contract to supervise the building of a railroad

between Moscow and St. Petersburg. During the construction, Thomas Winans

and his team stayed in Alexandroffsky, a town outside St. Petersburg.

© 2024 Morris A. Pierce

Si