|

Chronological List of District Heating Systems in

the United States | District Heating

Studies | District Heating in

Rochester, New York |

District Heating Summary Document (pdf)

District heating could

not be introduced until heating apparatus had been developed for

individual buildings. These systems included hot air, hot water and

steam and were slowly adopted during the 19th Century.

References about

Building Heating Systems

1594 The

jewell house of art and nature. Conteining divers rare and profitable

inventions, together with sundry new experimentes in the art of

husbandry, distillation and moulding, by [Sir Hugh Plat]

1739 "Nytt påfund af Drif-bänkar, som undfå sin Wärma af Anga" [A new experiment with hot-beds heated by steam.] by Mårten Triewald, Svenska Vetenskap Academiens Handlingar [Transactions of the Swedish Academy of Sciences] 1:25-35 (July, August, September, 1739).

1794 The

Repertory of Arts and Manufactures 1:300-303

"Specification of the Patent granted to Mr. John Hoyle, of the Parish of

Halifax, in the county of York, Dyer; for his Method of communicating Heat

to Green-Houses, Churches, Dwelling-Houses, and all other buildings,"

dated July 7, 1791.

1801 The

Picture of Petersburg, by Heinrich Friedrich von Storch

Page 50: The Tauridan Palace. The heat is maintained by

concealed flues practised in the walls and pillars, and even under the

earth leaden pipes are conveyed, incessantly filled with boiling water.

1813 "Letter

from Oliver Evans to his son George, May 19, 1813," reprinted in Oliver

Evans: A chronicle of Early American Engineering, by Greville

Bathe and Dorothy Bathe (1935)

Page 193: I have conceived a great improvement in the application of

my inexhaustible principle of my Steam engine I warm a factory by

Conveying the Steam by light coper pipes through all the appartments so

that the Steam condensed to water will run back to the supply pump The air

itself will condense the steam with the aid of the pressure of the Steam

as the pipe fills and the hotter the supply water is returned to the

boiler to be raised the less by the fire say 30° only the less fuel will

be required because the difference between the elastic power of Steam in

the boiler and condenser will be greater and this difference is the neat

power of the engine.

At Patapsco near Baltimore they have a copper pipe run through all their

appartments enough to condense for 100 horse power and their boiler to

make the steam sufficient for a 20 or 30 horse engine the same fuel that

they use would drive the Engine to work their Machinery is not this

astonishing that this was not sooner seen in all the 7 years since I first

calculated the above table and explained it in a book. This will secure

our Steam engine 14 years perhaps longer but Mum.

1814 "An

Oliver Evans License of 1814," reprinted in Power

40(11):378-379 (September 15, 1914)

This engine is not more than one fourth the weight of others; is more

simple, durable, and cheap, and more suitable for every purpose;

especially for propelling boats and land carriages. It requires no more

water than the fuel will evaporate in steam, and this steam may be

employed to warm the apartments of factories; or the condenser could be

used as a still to distil spirits; or a vat or paper making, boiler in a

brewery, dye factory, &c. &c.

1828 "Upon the Application of Hot Water in Heating Hot-houses," by Mr. Thomas Tredgold, Read August 5, 1838, Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London 7:568-583 (1830)

1828 "Mr.

Atkinson of Grove End Proved to have been the First who successfully

applied the mode of heating by hot water to hot-houses," by Thomas

Tredgold, The Gardener's Magazine, and Register of Rural and Domestic

Improvement 3:427-432 (March 1828)

Page 430: It is probable, also, that the circulation of hot water in

the conservatory of the Palace of Taurida, mentioned by Storch, in his

Description of St. Petersburgh, as having been in use in the time of

Prince Potemkin was effected by some French engineer who had seen the

invention of M. Bonnemain.

1831 "Review

of Upon the Application of Hot Water in Heating Hot-houses by Mr. Thomas

Tredgold," The Gardener's Magazine and Register of Rural &

Domestic Improvement 7:177-187 (April 1831)

It is an undeniable fact that the first discoverer was Bonnemain

1831 "Extract

of a letter from Col. Thomas H. Perkins," New England Farmer

10:156 (November 30, 1831)

Description of a hot water heating apparatus for his hothouse.

1832 "Perkin's Apparatus for Heating Air," Journal of the Franklin Institute of the State of Pennsylvania 10:45-49 (July 1832)

1836 Principles of Warming and Ventilating Public Buildings, Dwelling Houses, Manufactories, Hospitals, Hot-houses, Conservatories, &c: And of Constructing Fire-places, Boilers, Steam-apparatus, Grates, and Drying-rooms; with Remarks on the Nature of Heat and Light, &c. &c. &c, by Thomas Tredgold, Third Edition

1837 A Popular Treatise on the Warming and Ventilating of Buildings, by Charles James Richardson | Second Edition (1839) |

1837 On the comparative merits of the various systems of warming buildings by means of hot water, by W. Walker (of the Firm of Turner and Walker, Dublin.)

1840 A. M. Perkins's improved patent apparatus for warming and ventilating buildings, by Angier March Perkins

1841 Report

on Perkins's System of Warming Buildings by hot water, by John

Davies

Report on fires caused by the high temperatures of the Perkins apparatus.

1841 "On Warming Buildings by Hot Water," The Annals of Electricity Magnetism and Chemistry and Guardian of Experimental Science 6:475-499 (March 1841)

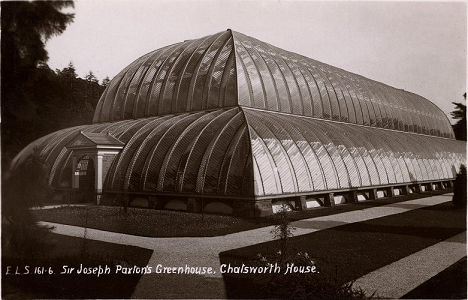

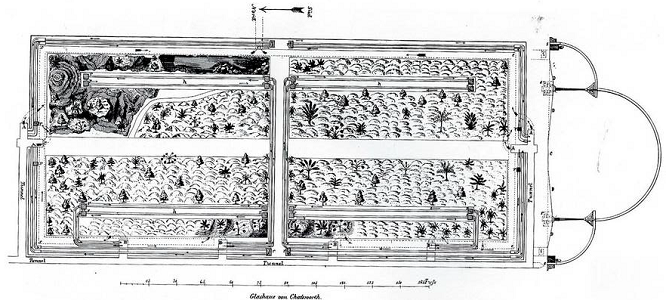

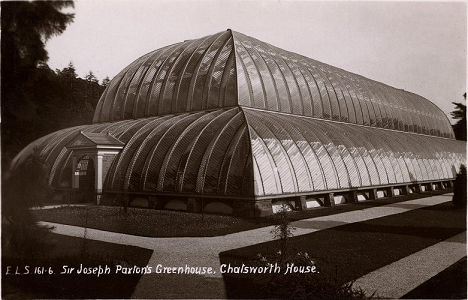

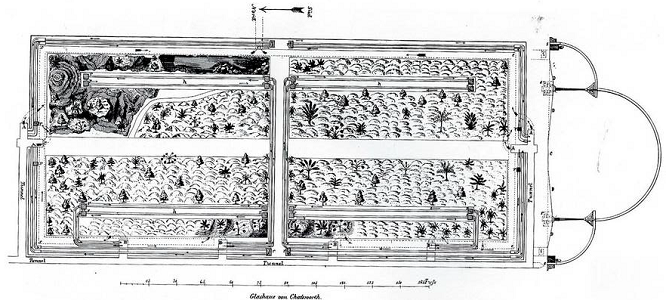

1841 Joseph Paxton's greenhouse at Chatsworth, known as the "Great Stove," was warmed with a hot water system with eight subterranean boilers.

|

|

| Joseph Paxton's Great Stove at Chatsworth | Plan of the Great Stove Heating System |

1841 “A

Description of the Eastern Penitentiary, of the State of Pennsylvania,

designed and executed by John Haviland, Esq., Architect,” by T.U.

Walter, Journal of the Franklin Institute 3rd ser. 2:118-120

(August 1841)

Page 119: The whole prison is warmed on Perkin's plan of hot water

circulation through iron pipes, and those who have the management of the

institution seem to be satisfied that the plan is a good one for such an

establishment.

1845 On the History and Art of Warming and Ventilating Rooms and Buildings, Volume 1, by Robert Stuart [Meikleham] | Volume 2 |

1846 A Novel Heating Installation - The Pulsial System - as installed at the New Premises of W.H. Smith & Son, Kingsway, London, by A.M. Perkins and Son Ltd.

1851 Walworth,

Nason & Guild's Catalogue of Wrought Iron Pipes and Iron and Brass

Fixtures for steam, gas, water, &c

Page 3: Walworth, Nason & Guild are the originators of the plan

of warming buildings, heating, drying, &c., by steam,

through the means of wrought iron pipes.

Pages 41-45: Warming by Steam

The exhaust steam from an engine can be applied efficiently for warmng by

this method; a simple device having been contrived to prevent the exhaust

from backing upon the engine.

1853 The Crystal Palace was rebuilt at Sydenham and designed to be opened year-round, which required a heating system, which was modeled after the one in the Great Stove.

|

| Aerial view of the Crystal Palace in 1936 |

1854 Guice

to the Crystal Palace and Park by Samuel Phillips

Pages 30-32: Hot Water Apparatus

The building was dismantled and reassembled in Sydenham with a new heating

system with eleven pairs of boilers placed twenty-four feet underground.

1855 Descriptive notice of the steam heating apparatus, by Stephen J. Gold

1858 Gold's patent steam heating apparatus : for warming private residences, stores, churches, hospitals, public buildings, green houses, graperies, &c., by Massachusetts Steam Heating Company.

1859 "Heating

Apparatus," The Baltimore Sun, December 16, 1859, Page 2.

The Annapolis Gazette states that Messrs. Hayward, Bartlett & Co., of

Baltimore, have completed the heating apparatus for the State House, and

it is now is successful operation. The heating agent is hot water; and the

effect Is really surprising. Even the large and lofty rotunda--the coldest

place this side of Canada--is as comfortably warm as the chilliest mortal

can desire.

1860 "The

New Government Building," Chicago Tribune, August 4, 1860,

Page 1.

Hot water heating apparatus is being put in under contract with Hayward,

Bartlett & Co., of Baltimore.

1862 "The

New United States Court-House," The Baltimore Sun, May 17,

1862, Page 1.

The whole structure will be heated by the hot water apparatus of Hayward,

Bartlett & Co.

1893 "The Early Days of Steam Heating," by James J. Walworth and A.C. Walworth, The Engineering Record 28:46 (June 17, 1893) | Part 2: 28:64 (June 24, 1893) |

1895 "A Short Talk on the Construction of Hot Water Radiators," Heating and Ventilation 5:3 (February 1, 1895)

1911 "Retrospective,"

by Edward P. Bates, Domestic Engineering 57:226-229 (December 2,

1911)

History of Walworth & Nason.

1913 "The Development and Application of the Steam Trap," by William H. Odell, Steam 11:68-70 (March 1913)

1945 Walworth 1842-1942

1960 The Beginnings of a Century of Steam and Hot Water Heating by the H.B. Smith Company, by Susan Reid Stifler

1961 The

Works of Joseph Paxton, 1803-1865, by George F. Chadwick

Pages 94-95: The first operation on the site was that of levelling

and excavation for the foundations and for the heating chamber beneath the

structure, and for the access tunnel beneath the cascade, for it was a

matter of principle with Paxton that the service aspects of the building

should be entirely invisible and the conservatory present the same aspect

to the gardens on all four sides; even the boiler flue was taken,

underground, up the hillside for some distance into the woods to an

isolated chimney-stack for this reason, a procedure that would result also

in increased draught for the furnaces; both flue and stack still survive.

Page 97: The heating of the conservatory was effected by no less

than eight boilers beneath the building, feeding seven miles of four-inch

iron pipe running in corridors high enough for a man to walk upright in

them. The fuel for the boilers was also stored underground, and fed to the

furnaces by a small tramway.

Page 148: As with many of Paxton’s building some of the most

interesting features were hidden from normal view, but not thereby lacking

in importance. Ventilation had been important for the Great Exhibition,

and to this was now added the need for heating. This Paxton patterned on

his successful experiments in low-pressure hot water heating at

Chatsworth. An access roadway ran through the basement storey of the

building, and here no less than twenty-two boilers were arranged in pairs,

each holding 11,000 gallons of water; one extra boiler was added at the

north end for a display of tropical plants, two in the lower storeys in

each wing, and two small ones for the fountain basins at each end of the

building containing Victoria regias and other tropical aquatics.

Four pipes of 9 in. diameter were attached to each boiler, two flow and

two return, and each boiler heated a certain transverse section of the

Crystal Palace: the length of one flow and return was a mile and

three-quarters, and the total length of heating pipes of all kinds was

nearly fifty miles. The control of this intricate system was said to be by

an unspecified new device invented by Paxton and Henderson.

© 2020-2024 Morris A. Pierce